Journal of Multidisciplinary Dental Research

DOI: 10.38138/JMDR/v5i1.1

Volume: 5, Issue: 1, Pages: 6-11

Original Article

Aravind Babu1 , K.C Ponnappa2, M.C Ponappa3, Salin Nanjappa A4.

1Conservative Dentistry & Endodontics. Private Practioner.

2Professor and Head of Department, Department of Conservative Dentistry & Endodontics.

3Professor, Department of Conservative Dentistry & Endodontics.

4Senior Lecturer, Department of Conservative Dentistry & Endodontics.

Corresponding author

Dr. Salin Nanjappa A

Senior lecturer Department of Conservative Dentistry & Endodontics.

Coorg institute of Dental Sciences Virajpet - 571218

Mobile no : 8762923732

Email: [email protected]

Received Date:02 January 2019, Accepted Date:25 February 2019, Published Date:05 March 2019

Introduction: The primary goal of successful restorative treatment is the effective replacement of lost tooth structure and maintenance of the integrity of the restoration. The success of Resin composite restorations depends on many factors, including the degree of moisture control, the effects of shrinkage during polymerization and how well the resin is cured. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of two LED curing units on microleakage of posterior composite resins.

Methods: For determination of microleakage, standardized MO or DO box cavities were prepared on 50 human extracted premolar teeth which was divided into 5 groups. Control group were only acid etched but adhesive was not applied. All other groups were etched with 37% phosphoric acid for 15 seconds, rinsed for 30 seconds with water and blot dried, adhesive was applied and light cured.

Results: FiltekTM Bulk fill composite cured with Valo curing light exhibited least microleakage when compared to all other groups.

Conclusion: The study showed that control group as well as other groups exhibited microleakage but FiltekTM Bulk fill composite resin showed lesser microleakage than Tetric N-Ceram.

Keywords: Bulk fill resin composite, polymerization shrinkage, curing lights, microleakage.

Resin composite is the most commonly used direct tooth-colored restorative material. Composite resins have gained popularity because of the increasing demand for esthetic restorations1.

For success and longevity of esthetic restorations, it is important that the restoration has a perfect seal2,3. Despite improvements in materials and techniques for light-cured composites polymerization shrinkage has remained a problem4,5.

There are many parameters that influence the degree of polymerization of composite resins such as their composition, shade and translucency, characteristics of the light-curing unit used, rate of curing and duration of photopolymerization6,7.

One of the reasons for the failure of composite resin is their insufficient polymerization. The compromised mechanical characteristics such as reduced hardness, microleakage, and secondary caries are the consequences of poor curing which leads to failure of composite restorations7.

The standard equipment used for polymerizing composite resins is conventional quartz tungsten halogen (QTH) light-curing units (LCU's). The limitations of these lights are degradation of the bulb, reduction of light intensity and the filter all of which may lead to incomplete polymerization. A light-emitting diode (LED) LCU's that produce blue light have been advocated for curing dental materials. LEDs produce less heat hence cooling fans is not required. The other advantages of LED are they are small in size and cordless and they can operate for thousands of hours with constant light output in power and spectrum8.

The study was done to evaluate the effect of two different LED curing units on microleakage of posterior composite resins.

Methodology

50 human premolar teeth which were caries-free were cleaned of calculus and debris and stored in normal saline as per OSHA regulations.

Two Resin composites used for the present study were FiltekTM Bulk fill composite restorative material (3M)( N614236) and Tetric N-Ceram

Bulk fill composite restorative material (IVOCLAR) (V39010). These resin composites were cured with Valo (3M ESPE) and Blue Phase (IVOCLAR) light curing systems. The adhesive used was Adper single bond and etchant used was 37% phosphoric acid.

On selected teeth, standardized Class II (MO or DO) box cavities were prepared with the following dimensions: Gingival seat width 1.5mm (MesioDistal) and 2.5mm (Bucco-lingual), depth of 1.5mm. The preparations were made with a No. 245 carbide bur under copious water coolant with the help of a high speed airotor handpiece. The control group comprising of 10 teeth were only acid etched, with 37% phosphoric acid for 15 seconds, rinsed with water for 15 seconds and excess water was removed with blotting paper, leaving a glistening hydrated surface. The other 40 teeth were acid etched, followed by application of Adper single bond adhesive to etched enamel and dentin and light cured.

GROUPS FOR MICROLEAKAGE STUDY: CONTROL GROUP

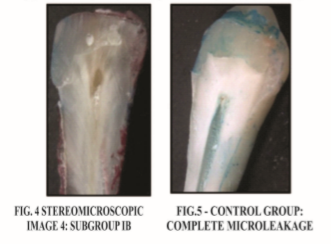

10 premolars were restored with FiltekTM Bulk Fill composite resin (without adhesive) and cured for 20 seconds in conventional curing mode with Valo and Blue Phase LED curing units respectively.

GROUP I (20 premolars)

SUB-GROUP IA

10 premolars were restored with FiltekTM Bulk Fill composite resin and cured for 20 seconds in conventional curing mode with Valo LED curing unit.

10 premolars were restored with Tetric N-Ceram Bulk Fill composite resin and cured for 20 seconds in conventional curing mode with Valo LED curing unit.

GROUP II (20 premolars)

SUB-GROUP IIA

10 premolars were restored with FiltekTM Bulk Fill composite resin and cured for 20 seconds in conventional curing mode with Blue Phase LED curing unit

SUB-GROUP IIB

10 premolars were restored with Tetric N-Ceram Bulk Fill composite resin and cured for 20 seconds in conventional curing mode with Blue phase LED curing unit.

The restoration were then finished and polished, and the specimens were washed under running tap water for 2 minutes and stored in distilled water at 37 degree Celsius for 2 weeks and then thermocyled at 1500 cycles between 5to 55 degree Celsius at a dwell time of 30 seconds, prior to testing for microleakage.

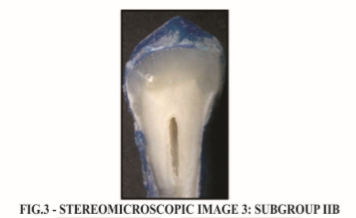

Apices of the samples were sealed with sticky wax, then teeth were painted with 2 coats of varnish, except for the restoration and 1 mm around the gingival margins and air dried. It was then immersed in 0.5% methylene blue for 24 hours. After removal from the dye, the samples were cleaned under running tap water for 2 minutes and were sectioned mesio-distally through the centre of the restoration with a water cooled diamond disk to obtain two sections from each tooth. Dye penetration was examined (both-halves) at the gingival margins using Stereomicroscope under 10X magnification.

Dye penetration was evaluated at the toothrestoration interphase based on the scoring criteria given below

RESULTS

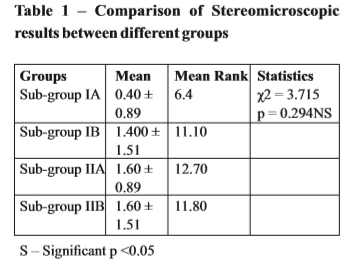

Table 1 shows comparison of stereomicroscopic results between different groups and sub-group IA exhibited microleakage with mean value of 6.4 followed by sub-group IB with a mean value of 11.10.

Sub-groups IIA and IIB exhibited values of 12.70 and 11.80 but after comparison with all other groups it was found to be non-significant with a p value of 0.294.

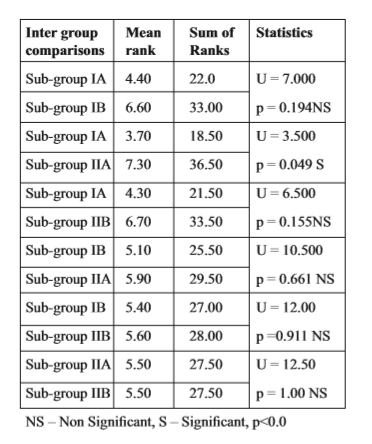

Table 2: Intergroup comparisons Stereomicroscopic results (Mann-Whitney)

DISCUSSION

In early 1960s Resin-based composites were first developed and provided materials with higher mechanical properties than acrylics and silicates.

Polymerization shrinkage is the biggest disadvantage of composite material which is responsible for the formation of internal stresses in the material and leakage between the filling and the walls of the cavity and formation of post-treatment sensitivity9.

Microleakage studies are the most common method of detecting the causes that result in bond failure along the tooth restoration interface. There are many methods for detecting marginal leakage and the organic dye method was chosen for this study because of its simplicity & extensive use in the literature.

0.5% basic fuchsin, 2% methylene blue and 50% silver nitrate are the routinely used dyes. The advantages of dye penetration assay are first, no reactive chemicals are used along with no radiation. Second, different dye solutions are available; therefore, the technique is highly feasible and easily reproducible10.

In the present study, the groups were restored with two different bulk fill composite resins such as FiltekTM Bulk Fill & Tetric N-Ceram Bulk Fill materials.

3M ESPE FiltekTM Bulk Fill posterior restorative material is a visible, light-activated restorative composite optimized to create posterior restorations simpler and faster. This bulk fill material provides excellent strength and low wear for durability11.

Tetric N-Ceram as a Bulk Fill posterior restorative material is gaining popularity throughout the world which can be applied in bulk layers of up to 4 mm, which reduces the number of increments required to place a restoration11.

In the present study, two LED curing units were used namely: Valo (Ultradent) & Blue Phase (Ivoclar-Vivadent).

Valo has ultrahigh energy broadband LED’s which can cure light cured dental materials. There are three curing options namely: Standard power, High power and Xtra Power which offer convenience and flexibility. It has a unique unibody design which is extremely durable and light weight. They produce high intensity light across 395-480 nm spectrum to polymerize all light cured dental materials.

It has LED chipset at the distal body end and directed perpendicular to the long axis of the body.12

Blue Phase has a slim and ergonomic design. They have a polywave LED with halogen like broad band spectrum of 385-515nm. They have a cordless or corded operation. They offer a large treatment field due to 10mm light probe.

It is a typical “gun” style light, containing the LED chip array in the nosecone of the gun, directing its light toward the proximal end of a fiber optic light guide, quite long in length, after the tip curve12.

In the present study, results of stereomicroscopic observation for microleakage between different groups and Filtek TM cured with Valo LED curing unit (subgroup IA) exhibited microleakage with mean value of 6.4, followed by Tetric N-Ceram cured with Valo LED curing unit (sub-group IB) with a mean value of 11.10

Filtek TM cured with Blue phase curing unit (sub-group IIA) and Tetric N-Ceram (sub-group IIB) exhibited values of 12.70 and 11.80 respectively, but after comparison with all other groups it was found to be non-significant with a p value of 0.294. The Intergroup comparison of stereomicroscopic results showed a statistically significant difference when Filtek TM cured with Blue phase (sub-group IIA) was compared with Filtek TM cured with Valo LED curing unit. (sub-group IA) with a p value of 0.049. This may be due to high intensity light produced by Valo LED curing unit with a wavelength of 395-480nm unlike Blue Phase LED curing unit which has a wave length of 385-515nm. Valo has 2 rodium coated reflectors inside the head to reflect more light and energy towards the restoration, ensuring optimum collimation of the light's beam and less loss of power over distance.

On evaluation of microleakage under stereomicroscope, Filtek TM cured using Valo LED curing unit (sub-group IA) exhibited lowest stereomicroscopic score followed by Tetric N Ceram cured using Valo (sub-group IB) then FiltekTM cured using Blue phase LED curing unit (sub-group IIA) and last Tetric NCeram cured using Blue Phase (sub-group IIB).

In the present study FiltekTM showed superior properties to Tetric N Ceram and this could be attributed to Valo LED light curing system which has shown to have better penetration depth.

Conclusion

Within the limitations of the methodology followed and procedures performed; following conclusions were drawn from this study:

Both Bulk fill resin composite materials FiltekTM and Tetric N-Ceram Bulk Fill exhibited microleakage.

There was significantly less microleakage for FiltekTM followed by Tetric N-Ceram.

Nanjappa SA et al., Comparative Evaluation Of The Effect Of Curing Lights On The Microleakage Of Posterior Resin Composite Restoration – An Invitro Study.2019:5(1);6-11

Subscribe now for latest articles, news.